-

(©Pino Musi)

(©Pino Musi)

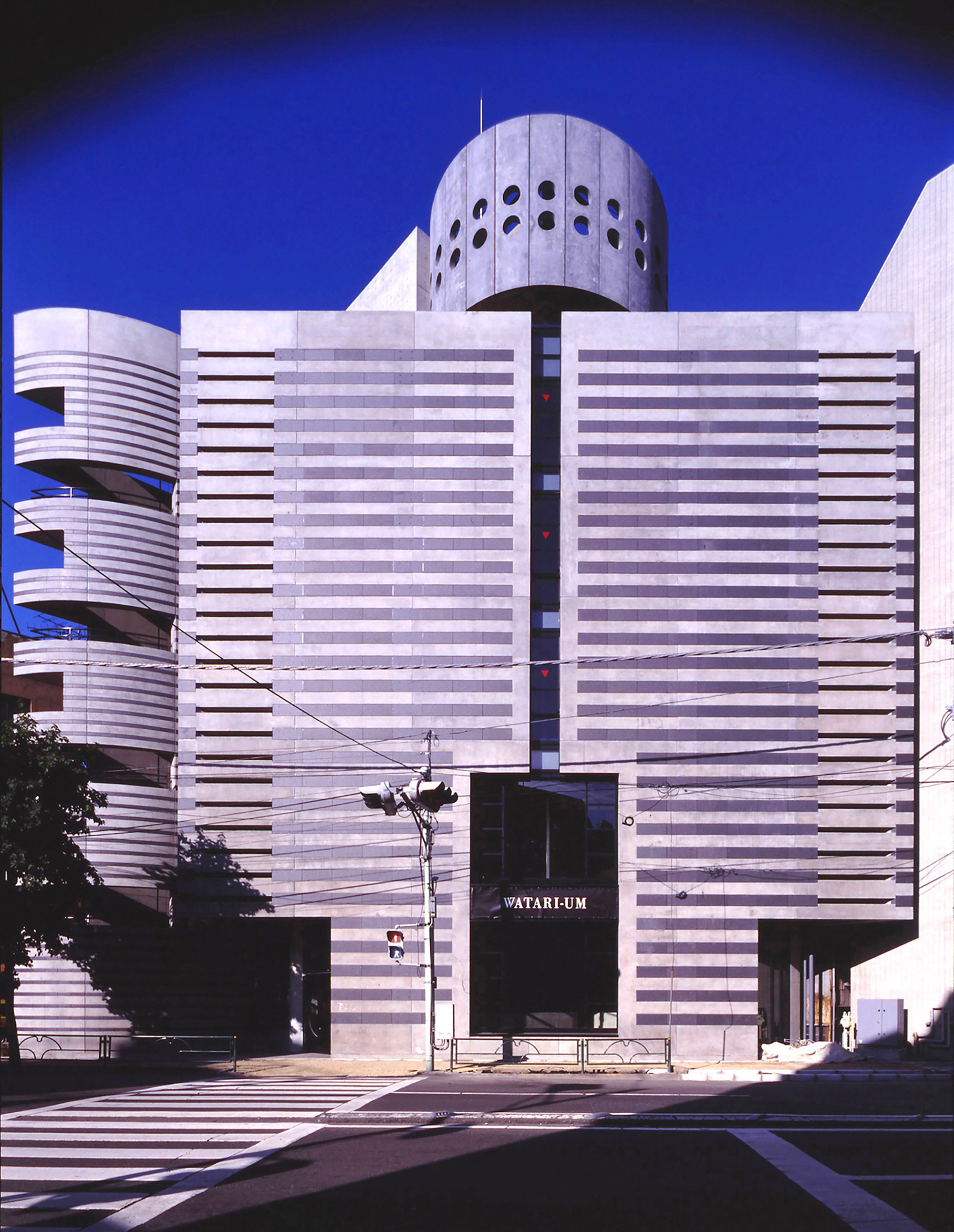

Watari Museum of Contemporary Art

Kanto | Tokyo - Shibuya Ward

Architecture & Design

Shibuya is home to many architectural landmarks. Few, however, are as easily recognizable as the one and only project built by acclaimed Swiss architect Mario Botta in Japan.

A distinctive structure for distinctive art

(©Pino Musi)

Conveniently situated a few minutes’ walk from the world-renowned Omotesando and Harajuku areas, the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art (WMCA) is home to curated seasonal exhibitions of contemporary art, photography, sculpture and industrial design. The works of numerous international and Japanese contemporary artists such as Ryuichi Sakamoto, Mike Kelley, Yayoi Kusama, or Gary Hill have been regularly featured in the curiously-shaped building, thanks to the help of notable curators such as Harald Szeemann (Kunsthaus Zurich). Swiss talents too have been invited on a regular basis, for example on the occasion of "Temporary Immigration", an exhibition on Swiss modern arts held in 2005.

(©Watari-um Museum)

Conceived as a stage for cultivating distinctive and new voices in the art world, the museum is however neither regionalist, nor internationalist in the sense that it is showing “whatever is considered important everywhere”. And this stance caught the attention of a rising Swiss architect, who would eventually give the WNCA building one of the Japanese capital’s most unique appearances.

Triangle-shaped plot

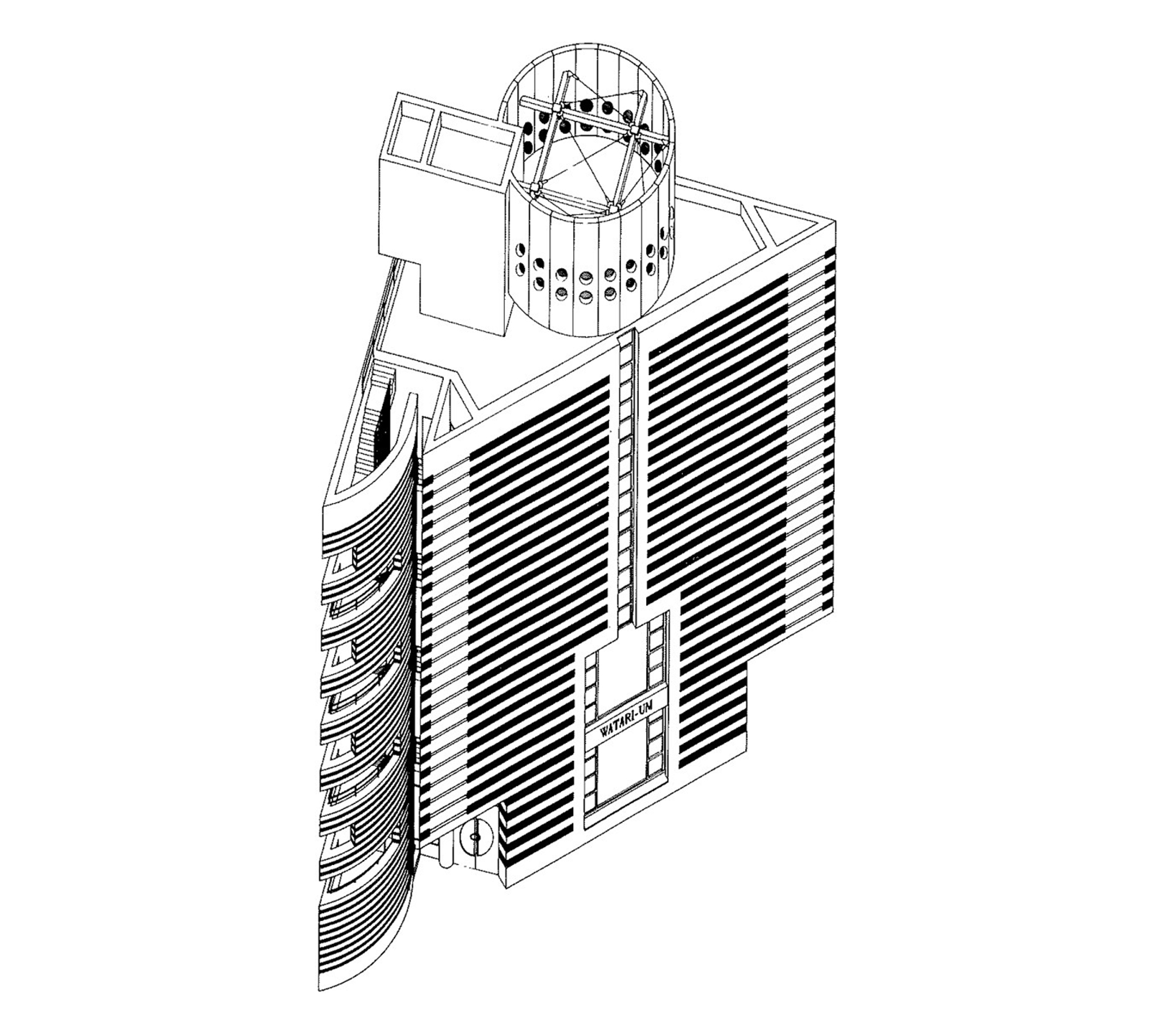

Watari-um axonometric projection

The WMCA was mandated in 1985 by Shizuko Watari (1932-2012), who since December 1972 had owned the Gallery Watari, located on the site of the current museum). Having visited the location under direct invitation of the curator herself, renowned Swiss architect Mario Botta quickly decided to take upon the challenge and started designing his first project in Japan.

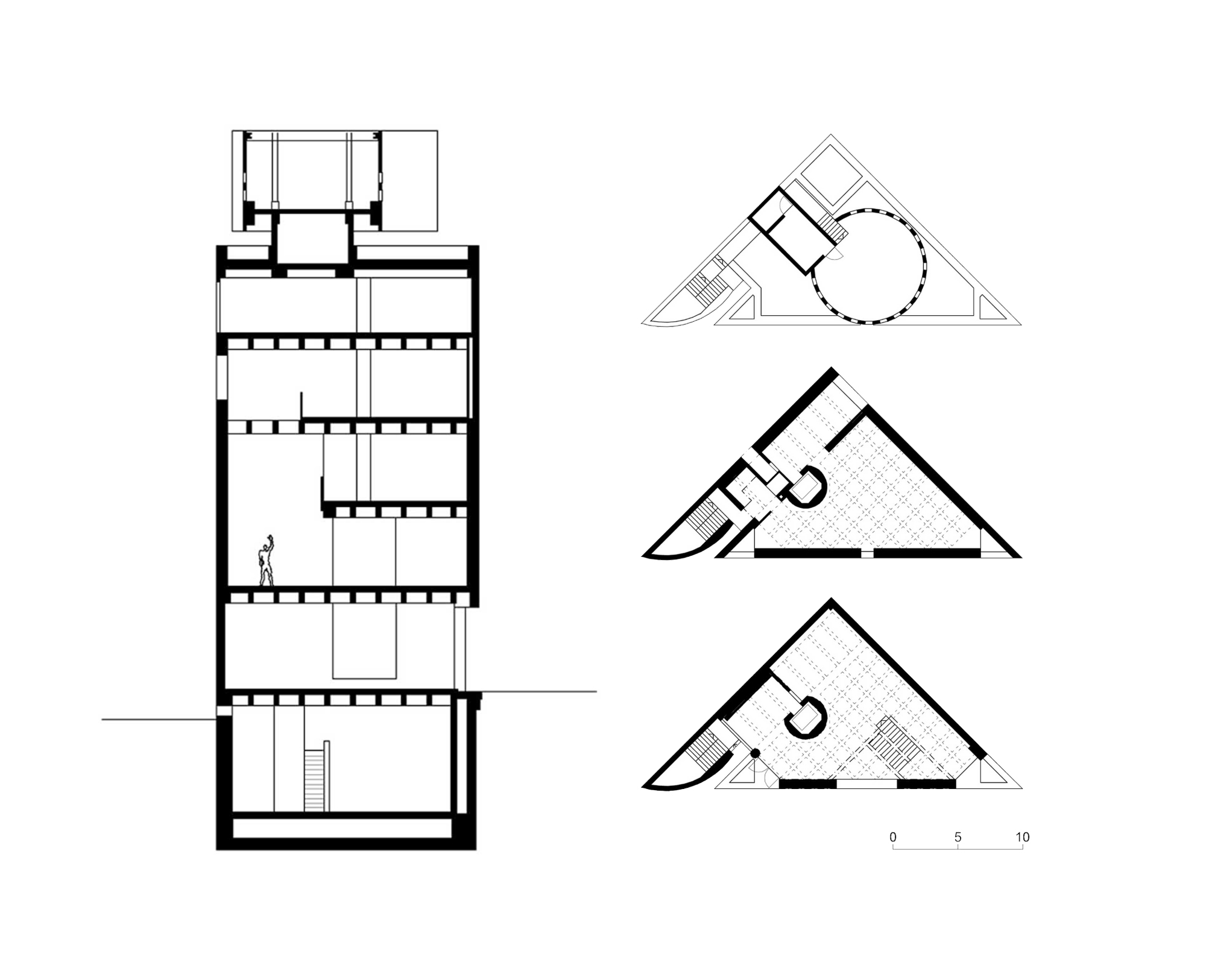

Watari-Um section and plans (©Mario Botta Architetti)

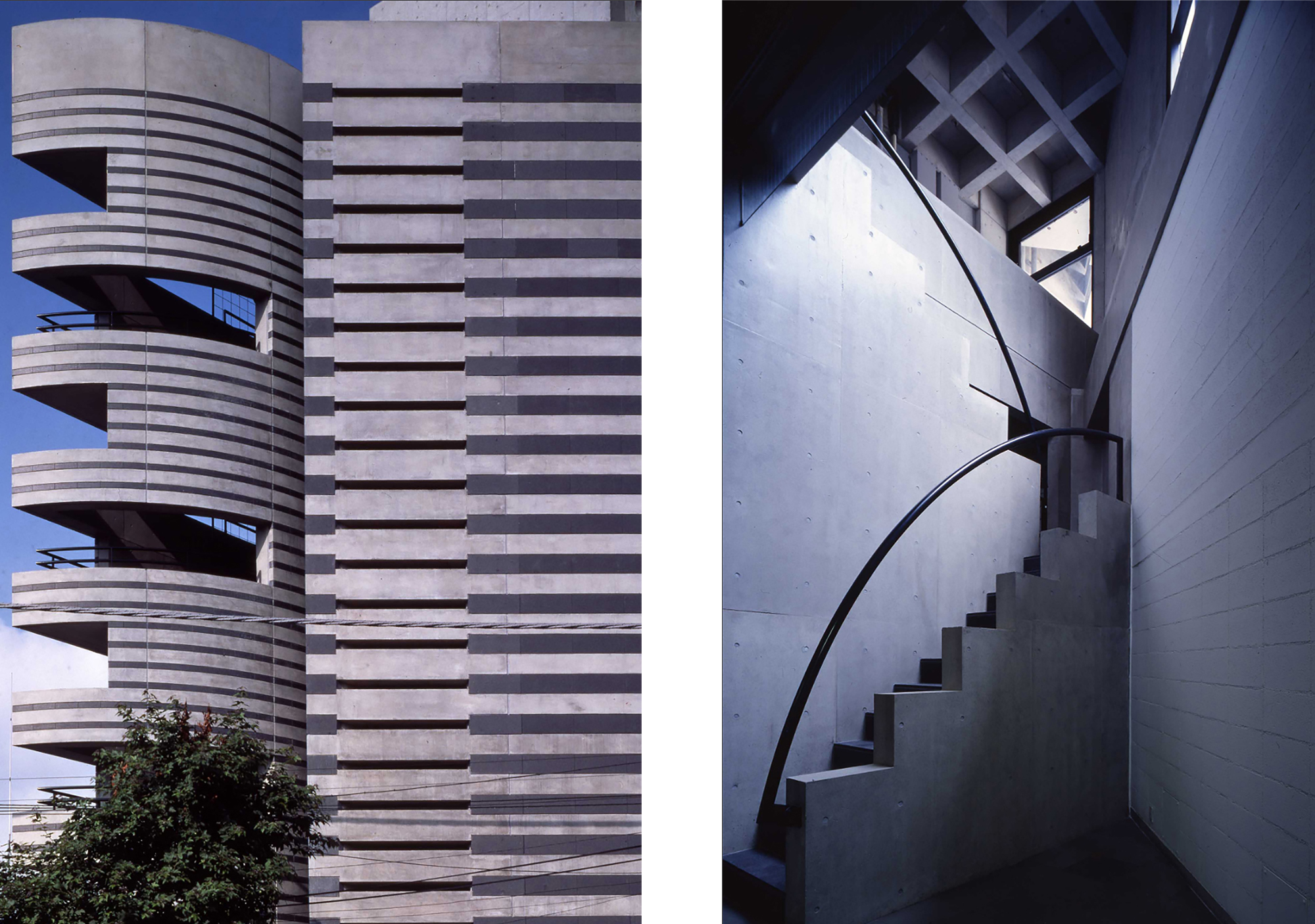

Constructed between 1988 and 1990, the WMCA is a 3,650 m3 triangular building and is confronted with three different spatial situations: a major thoroughfare, a side street and a smaller construction to the rear. The main façade is characterized by the alternation of black stone slabs with unfinished, precast concrete elements and by a long vertical cut ending at the base in a rectangular opening. The entry is on the corner where the front meets the cut-out silhouette of the emergency stairway. This latter is pushed outward, beyond the building's size, so to gain exhibition surface along the side walls. The upper part of the front is crowned by a technical facility: a cylinder made of concrete with circular windows.

(©Pino Musi)

The museum is articulated over five above ground levels and a basement, linked by a single vertical connection. The exhibition spaces are on the first three levels and, in spite of their limited dimensions, they appear larger thanks to the clear layout. Although unique in the Tokyo landscape, the WMCA is nonetheless highly consistent with the visual identity and philosophy developed by Mario Botta since the late 1960s.

(©Pino Musi)

From Ticino to the world

Born on April 1, 1943, in Mendrisio, in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, Mario Botta studied architecture in Italy, and had the privilege to work as an assistant to Le Corbusier and Louis I. Kahn. He later opened his own practice in Lugano in 1970.

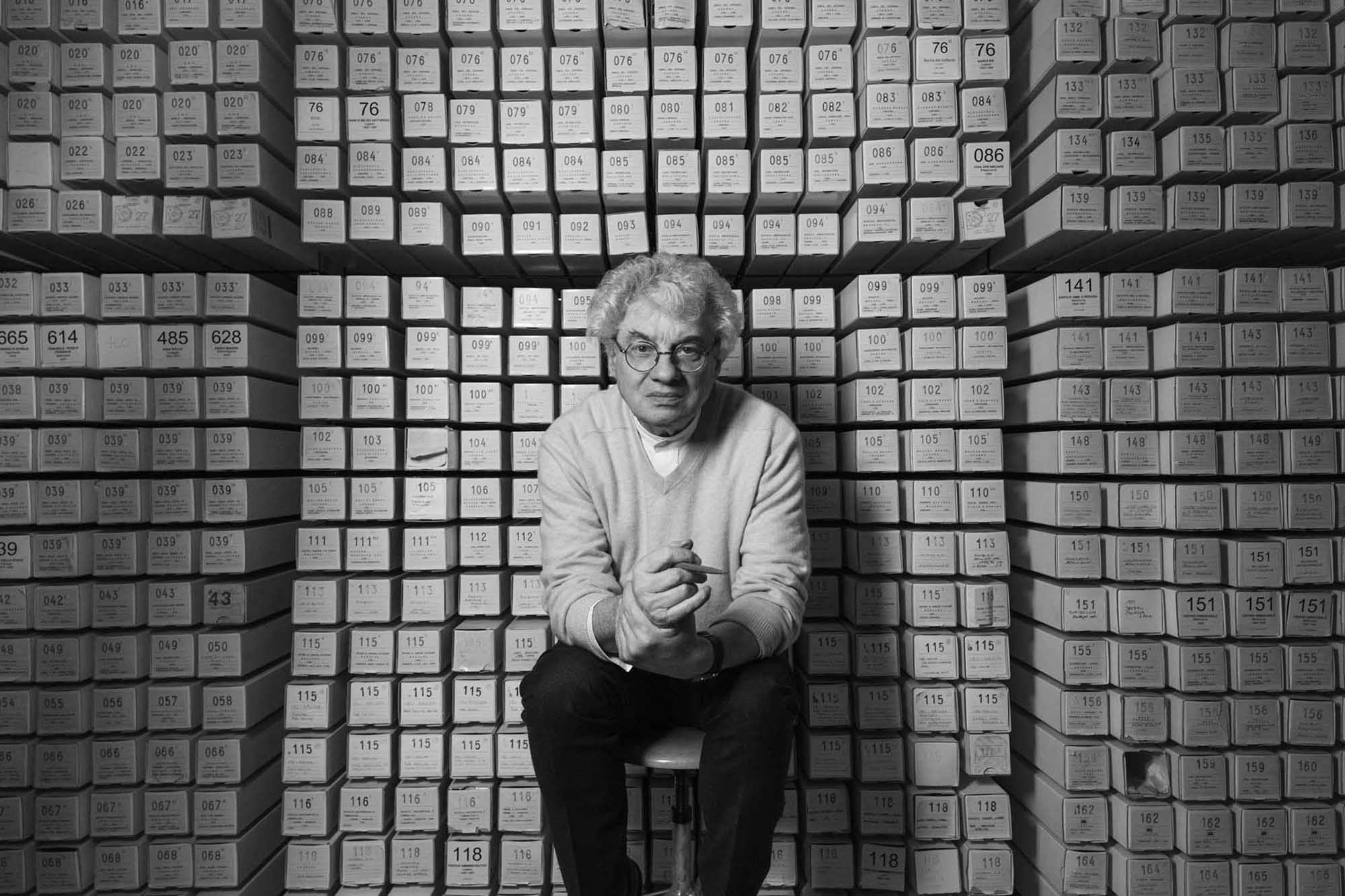

Architect Mario Botta (©Matteo Fieni)

Since then, Botta has stuck to a philosophy of historical determinism in which architecture acts as a mirror of its times. He is interested in history and in the study of man's habitat through time. Therefore, drawing its inspiration from modernism and the Tendenza (a neo-rationalist group), his style has attempted to reconcile traditional architectural symbolism with the aesthetic rules of the Modern Movement. The Swiss architect has also characteristically shown respect for topographical conditions and regional sensibilities and his designs generally emphasize craftsmanship and geometric order.

Church San Giovanni Battista, Switzerland (1996) (©Enrico Cano)

Although initially limited to the Swiss territory, Botta’s early projects such as the Capuchin convent in Lugano, the craft centre in Balerna and the state bank in Fribourg earned him international acclaim, and are still considered “must-see” for any architecture enthusiast visiting Switzerland.

Fiore di pietra, Monte Generoso, Switzerland (2017)

Since the second half of the 1970s, his houses have become more classical in plan and elevation, and in the 1980s he managed to secure countless commissions around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco or the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MART) in Rovereto, Italy. Whatever city you visit around the world, take a look at the building, and you might be lucky enough to recognize the Swiss architect’s signature stripes!

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco (1995)