-

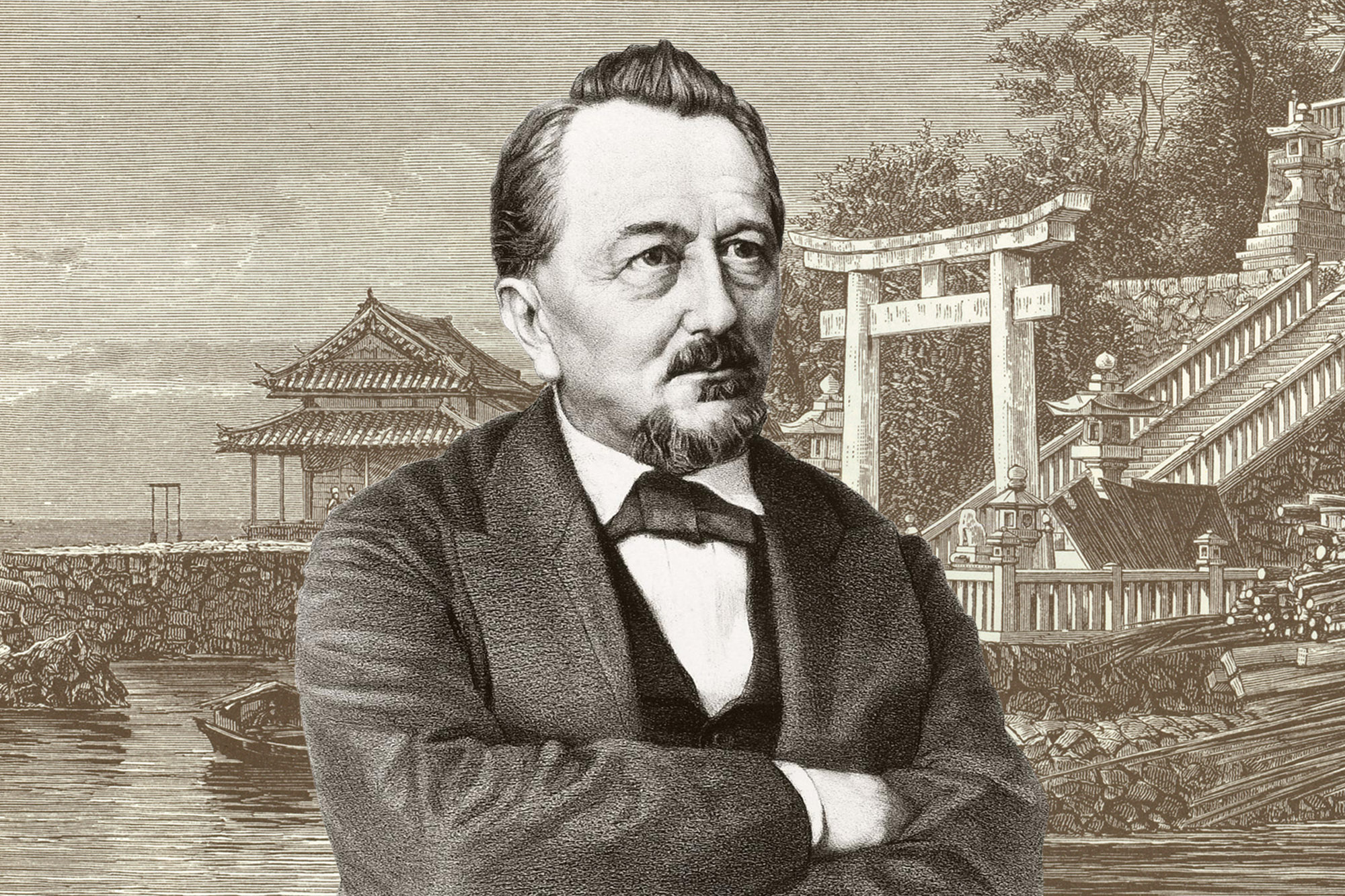

Front picture: Portait of Dr. Marcel Junod (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / s.d. / V-P-HIST-02894)

Front picture: Portait of Dr. Marcel Junod (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / s.d. / V-P-HIST-02894)

-

Dr. Junod visits the Stalag VII-A camp (Moosburg) with the camp's directors (©ICRC / s.n. / 10.11.1939 / V-P-HIST-00883-24).

Dr. Junod visits the Stalag VII-A camp (Moosburg) with the camp's directors (©ICRC / s.n. / 10.11.1939 / V-P-HIST-00883-24).

-

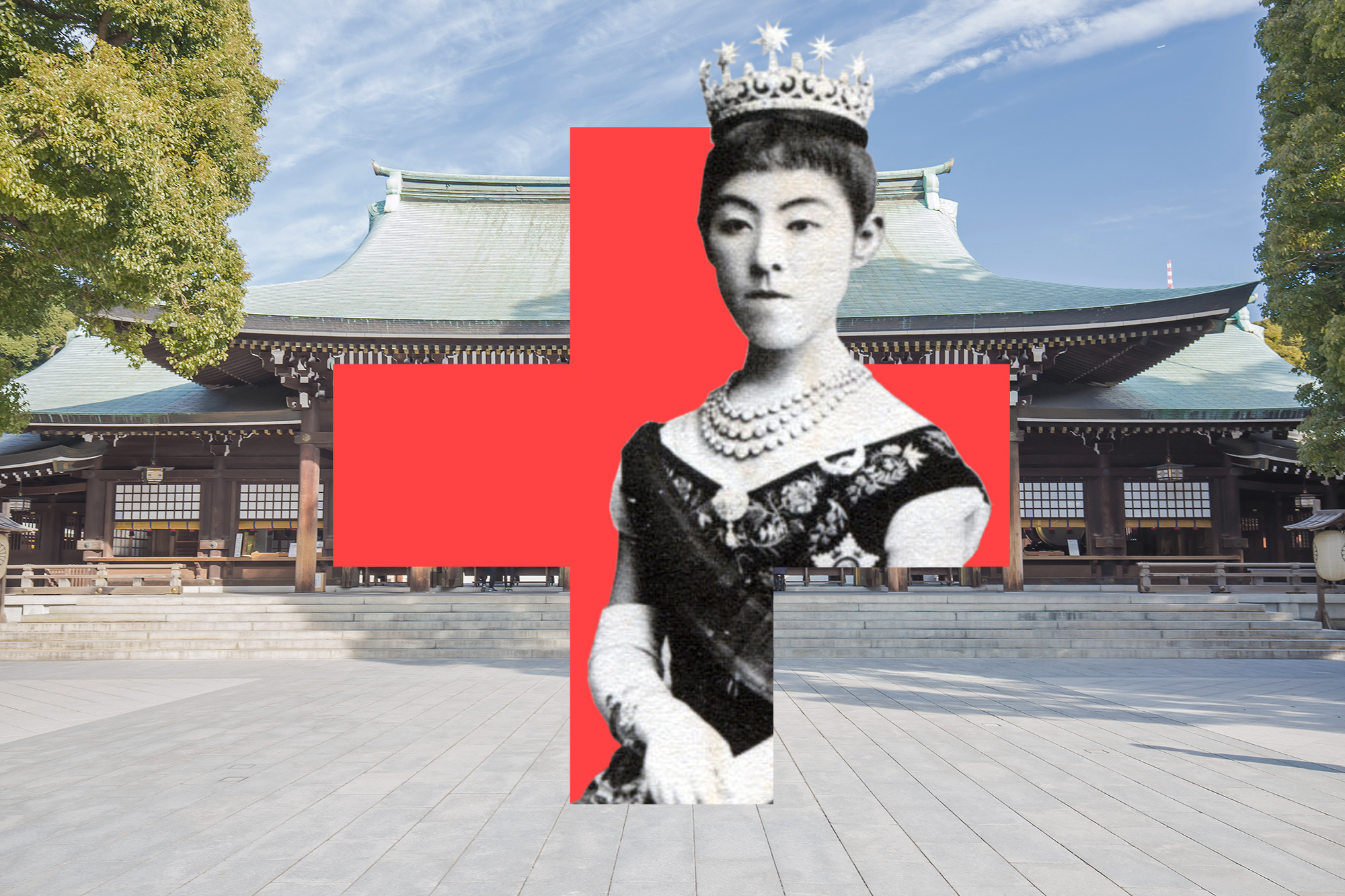

Commemorative Monument to the late Dr. Junod, in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (©ICRC archives - ARR / CHESSEX, Luc / 06.1995 / V-P-HIST-E-00163).

Commemorative Monument to the late Dr. Junod, in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (©ICRC archives - ARR / CHESSEX, Luc / 06.1995 / V-P-HIST-E-00163).

Marcel Junod (1904-1961)

Chugoku | Hiroshima

Historical Figures & Locations

“Those who call for help are many. It is you they are calling.” – Marcel Junod, 1982

Fateful Monday

It was just another warm sunny summer morning in Western Japan. At 8:15 AM, however, locals noticed something rather unusual: a sudden brilliant flash of light, followed by an unusually loud booming noise. A few seconds later, the area was almost entirely razed to the ground by a firestorm, instantly ending tens of thousands of lives. That day was August 6, 1945, and the first atomic bomb had just been dropped on Hiroshima City. Three days later, the city of Nagasaki suffered a similar fate.

Hiroshima after the explosion of the atom bomb (©ICRC archives - ARR / NAKATA, Satsuo / 08.1945 / V-P-HIST-00260-08).

Due to the confusion that reigned in Japan in the final days of the Asia-Pacific War and to the blackout soon imposed by the Allied High Command, information on the scale of destruction in Hiroshima remained scarce. On site, the city’s medical personnel was overwhelmed by the scale of the disaster. They did not know how to treat patients with acute radiation syndrome, and a deadly typhoon made the matter worse a few days after the bomb.

White Cross, Red Cross

Marcel Junod as an intern in Mulhouse (©Benoît Junod, Switzerland)

Luckily, photographic evidence and information on what had happened in Hiroshima found their way to a Swiss doctor who had recently landed in Japan. Appalled by what he learnt, he assembled an unscheduled assistance mission and rushed to Hiroshima, where he was the first foreign doctor to arrive on September 8. His name, Junod, would never be forgotten.

Dr. Junod posing in front of an aircraft during the Ethiopian War (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / 1935-1936 / V-P-HIST-E-07037).

Born in Neuchâtel in 1904, Marcel Junod grew up in Switzerland and spent most of his twenties practicing medicine. At age 31, he became a field delegate for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which was created in Geneva in 1863 with the mission to provide humanitarian protection and assistance for victims of war and other situations of violence. During the next decade, Dr. Junod traveled to war-torn Ethiopia, Spain, Germany or Poland, where he often risked his life to protect vulnerable populations and prisoners of war. Many of his ICRC colleagues died along the way, and he witness countless cases of looting, indiscriminate bombings, and use of mustard gas on civilian populations.

Dr. Junod on the road from Valence to Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / 1937 / V-P-HIST-01849-18).

Dr. Junod meets the representative and the interpreter of the French prisonners at the Stalag VII-A camp, in Moosburg (©ICRC / s.n. / 10.11.1939 / V-P-HIST-01717-07).

In 1945, Dr. Junod flew to his next destination, Japan, with the mission to ensure that prisoners of war would be treated according to international conventions. History, however, had other plans for him.

Dr. Junod visiting the Japanese office of prisoners of war in Tokyo (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / 08.1945 / V-P-HIST-00261-09A).

Accompanied by an American investigation task force, two Japanese doctors, and 15 tons of medical supplies, Junod visited all the improvised hospitals of the region, administrated the distribution of materials, and personally took part in urgent medical care as a surgeon, saving the lives of many. The mission was a turning point: it provided the local medical staff with the necessary means to treat the victims. The Swiss doctor also gathered the first pictures of the disaster and sent them to the ICRC, which distributed them all over the world.

From Hiroshima to eternity

Dr. Junod overseeing the Japanese Koreans repatriation mission in Niigata (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / 08.1959 / V-P-HIST-E-03876).

Having returned to Tokyo five days later, Junod started putting down his haunting experience in a text that would later be published by the ICRC in 1982 under the name “The Hiroshima disaster”. In the 1950s, a failing health eventually forced him to return to Geneva, where he simultaneously practiced anesthesiology and held the positions of ICRC delegate and ICRC Vice President. After his passing on June 16, 1961, the ICRC received more than 3,000 messages of condolences.

Portait of Dr. Marcel Junod (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / s.d. / V-P-HIST-02893).

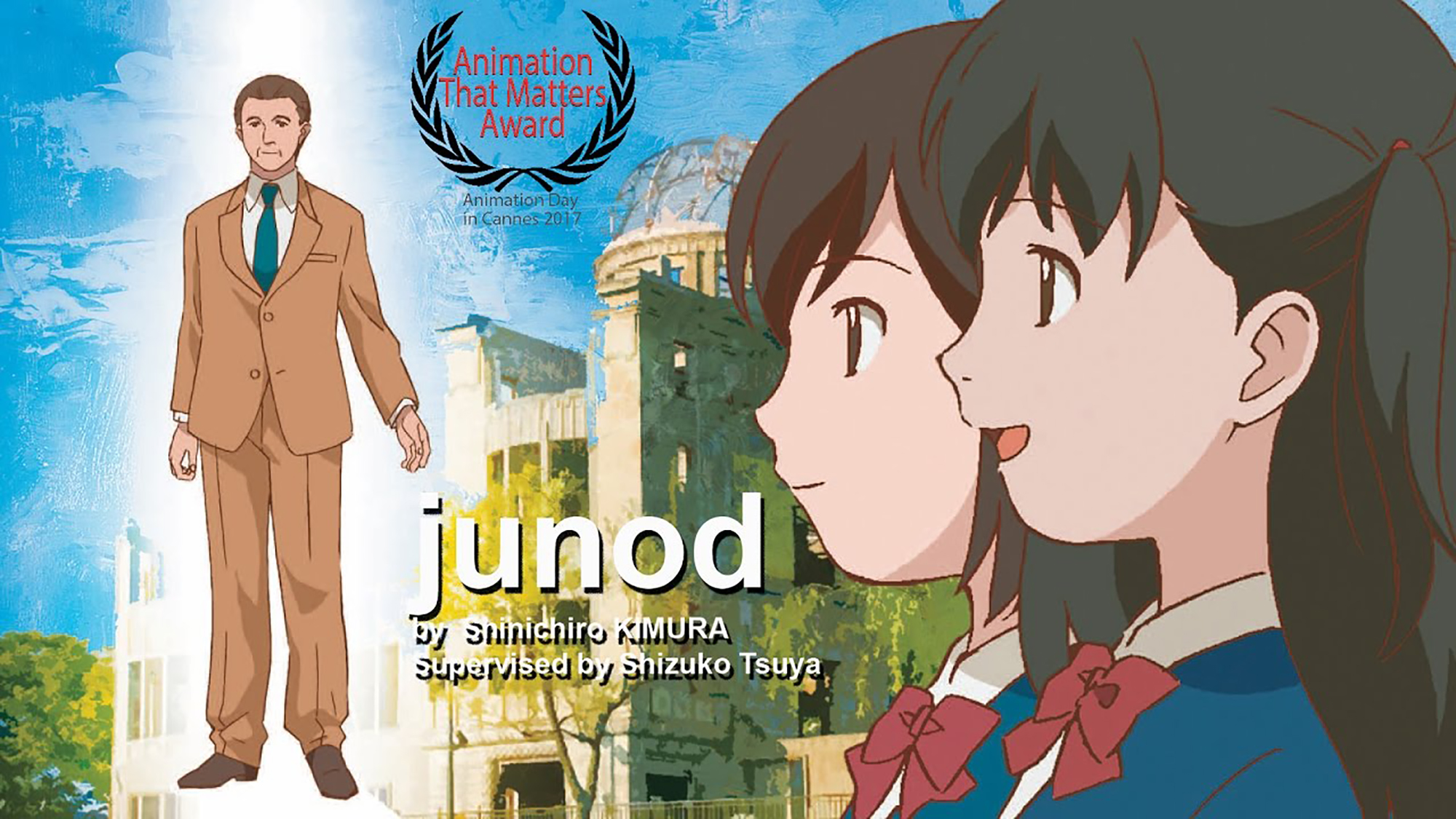

Dr. Junod might be gone, but his dedication to the people of Hiroshima in the midst of nuclear chaos was never forgotten by Japanese people. On September 8, 1979, a monument to his memory was inaugurated in the Hiroshima Peace Park, where a commemorative meeting is held each year on the anniversary of his death. More recently, in 2010, a 64-minutes long Japanese animation movie produced by Studio Hibari called “Junod” recounted the inspirational life and selfless actions of a man who helped people regardless of their backgrounds or origins.

Commemorative Monument to the late Dr. Junod, in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park (©ICRC archives - ARR / s.n. / 18.06.1995 / V-P-MON-E-00040).

"Junod" ("Dr. Junod"), released on May 11, 2010 (©Studio Hibari)

A humanitarian symbol

Today, the doctor remains an inspiration for many humanitarian actors around the world, such as the Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit, which has been deployed in response to many wars and disasters over the years, including the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011. Switzerland too, by promoting peacebuilding, human rights, international humanitarian law, and the rule of law, strives to follow his example.

The Swiss Humanitarian Aid Unit is active all over the world (©DDPS / Dominique Schütz / VBS/DDPS - ZEM Urheber).

In 2019, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the creation of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, the Embassy of Switzerland will launch a program called “Partners for Humanitarian Action”, which will highlight the two countries’ humanitarian cooperation through several activities including an academic symposium, an information campaign on social media, and a symbolic event organized together with the Japanese Red Cross Society. Of course, the symbol of the program will be none other than the good Dr. Junod himself.

Hiroshima has long recovered, and is today known as a city of peace.