-

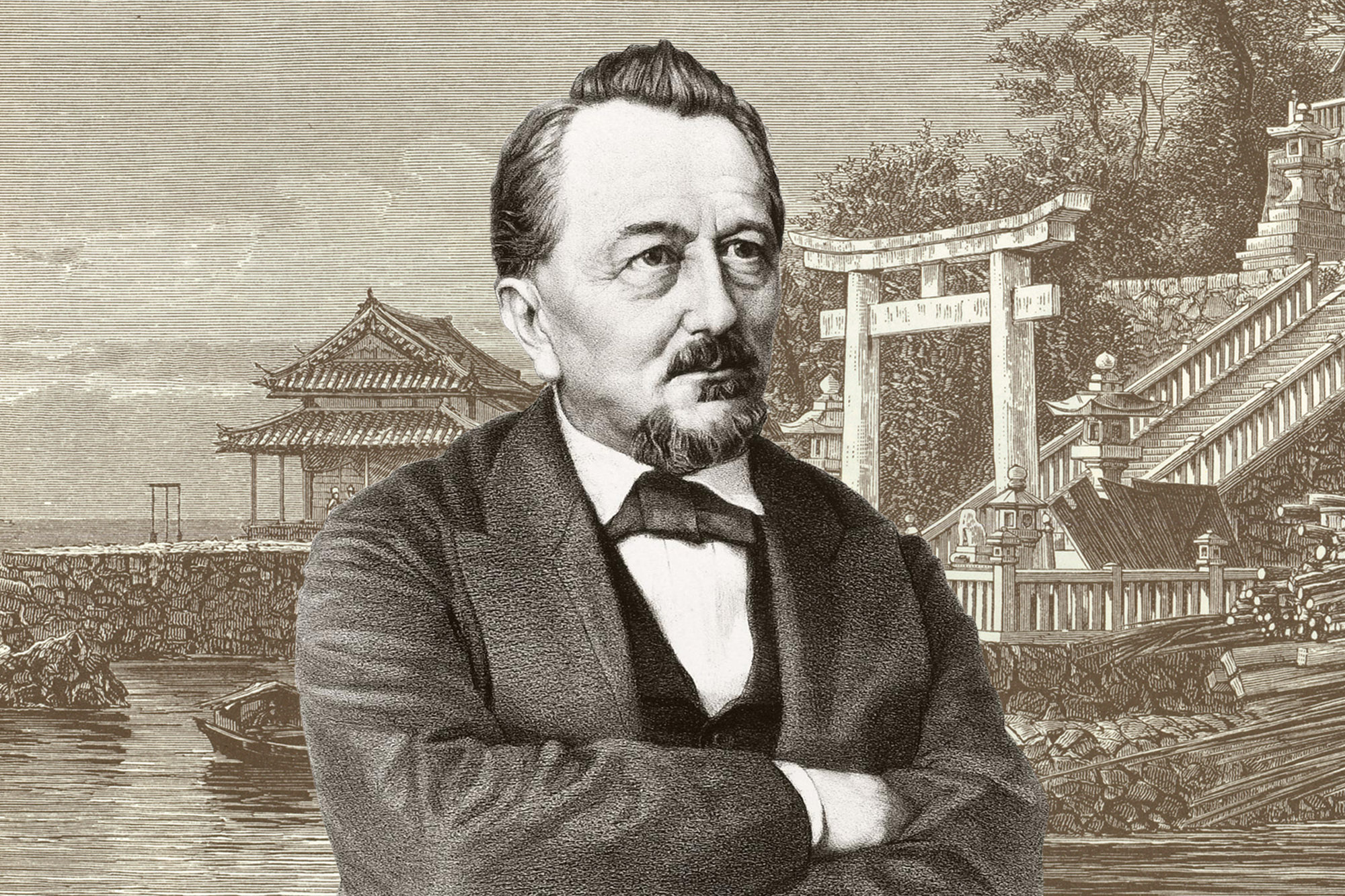

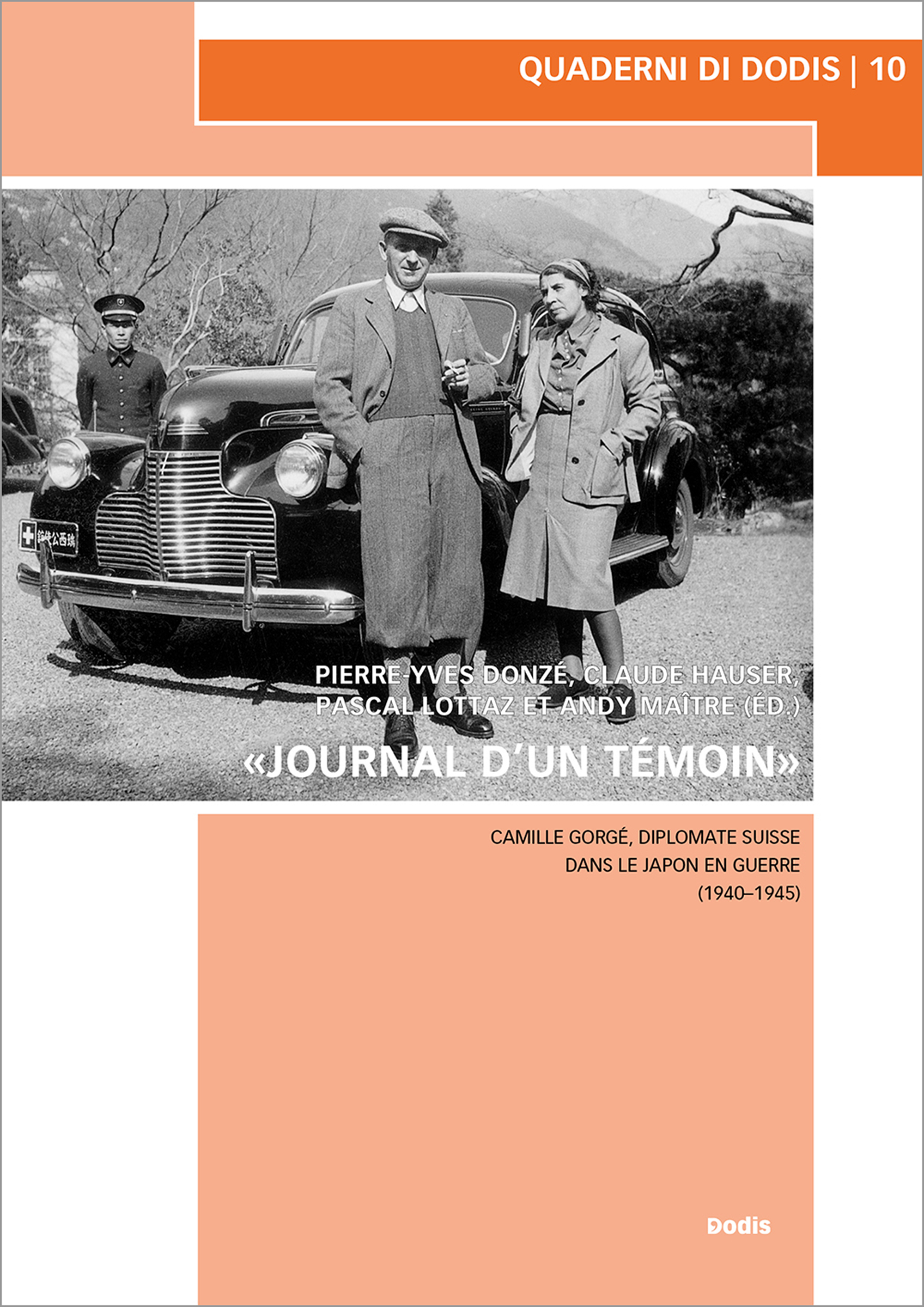

Front picture: Portrait of Camille Gorgé (©Gorgé family archives)

Front picture: Portrait of Camille Gorgé (©Gorgé family archives)

-

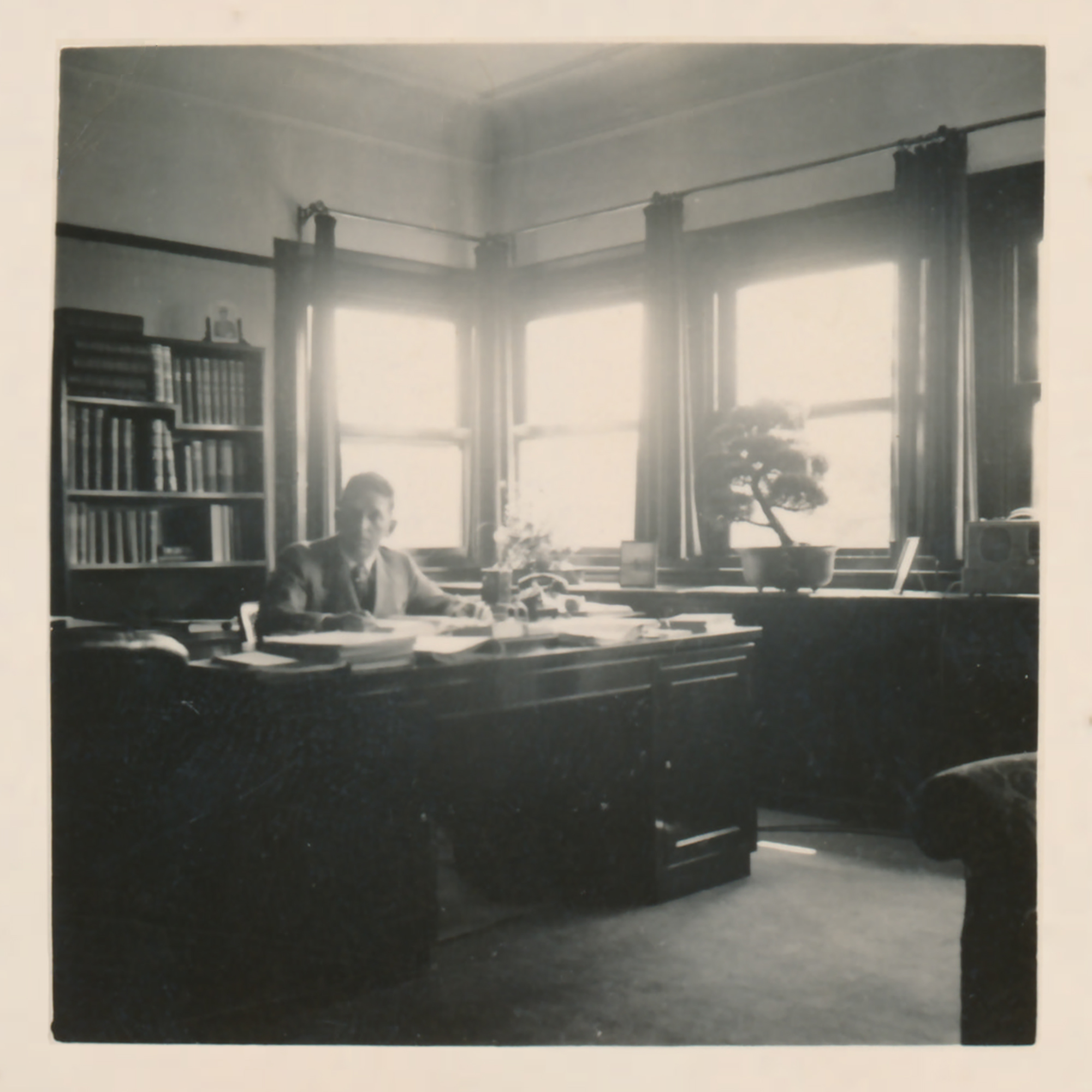

Minister Camille Gorgé in his office (©Gorgé family archives)

Minister Camille Gorgé in his office (©Gorgé family archives)

-

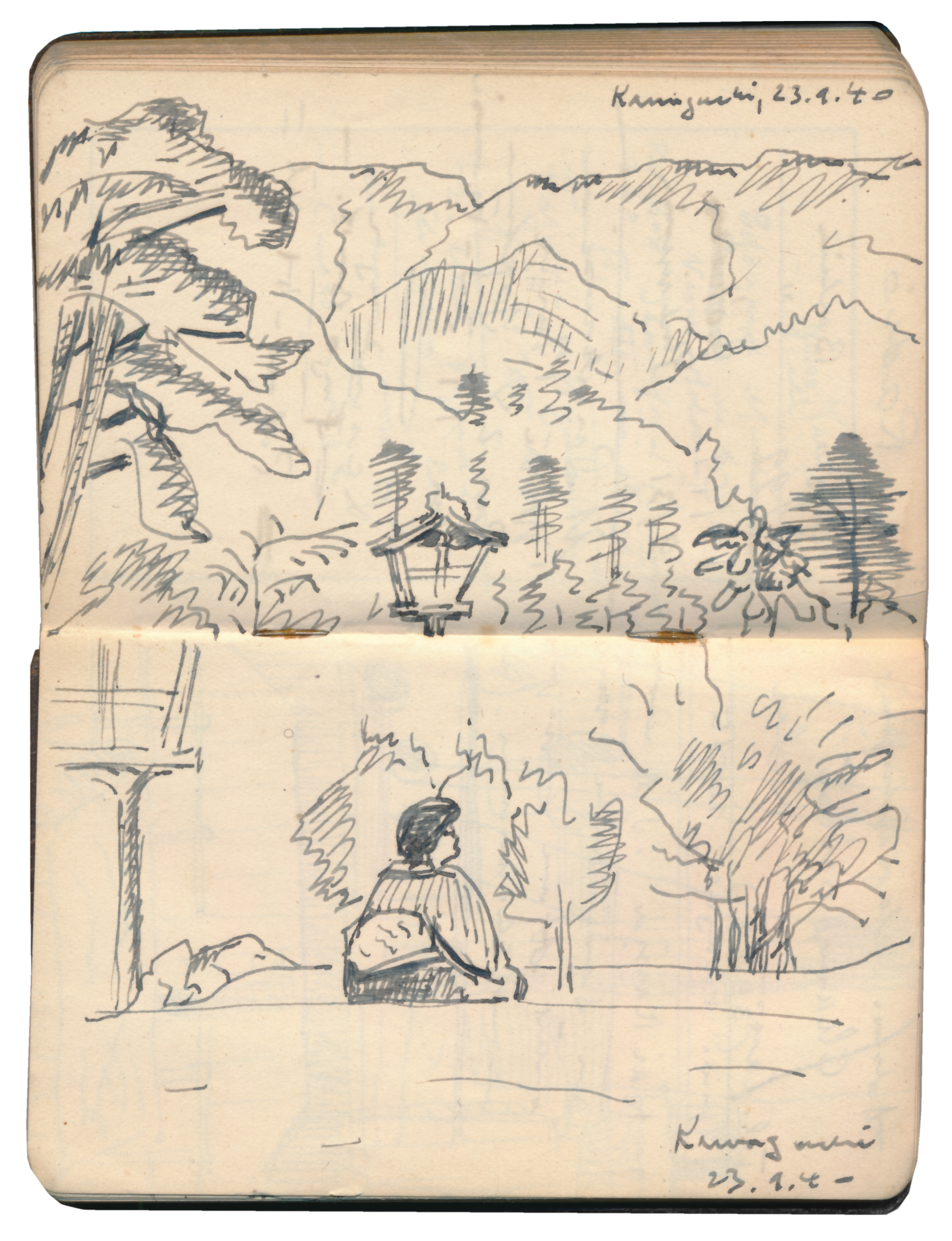

Camille Gorgé enjoying one of his favourite leisure activities: painting (©Gorgé family archives)

Camille Gorgé enjoying one of his favourite leisure activities: painting (©Gorgé family archives)

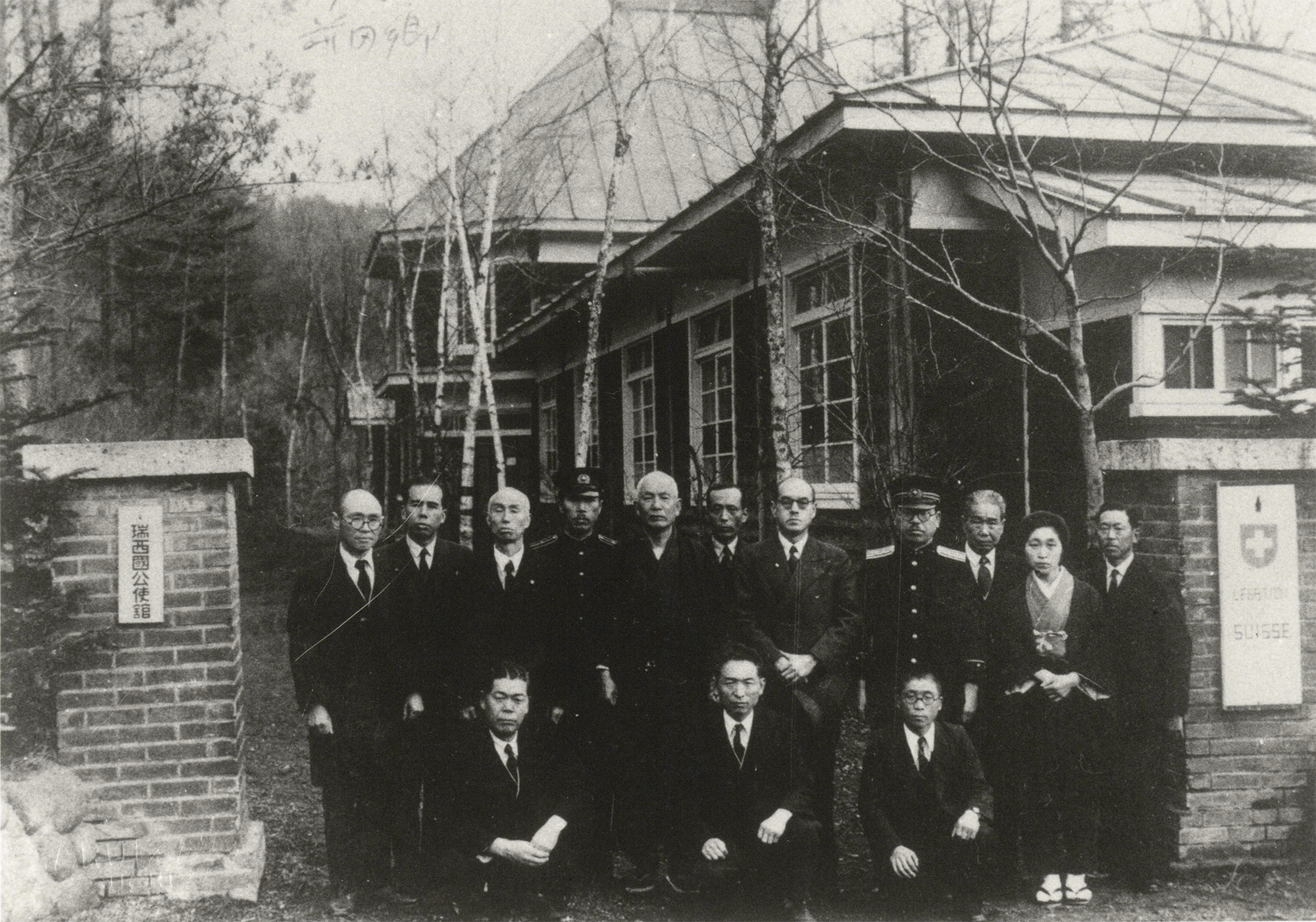

Former Swiss Legation in Karuizawa (1944-1945)

Chubu | Karuizawa Town

Historical Figures & Locations

Camille Gorgé’s deployment in Japan was supposed to be a highlight of his diplomatic career. From the Asia-Pacific War to Karuizawa, it indeed was one, albeit much more difficult than the Minister had initially envisioned it.

A Swiss Minister in Japan

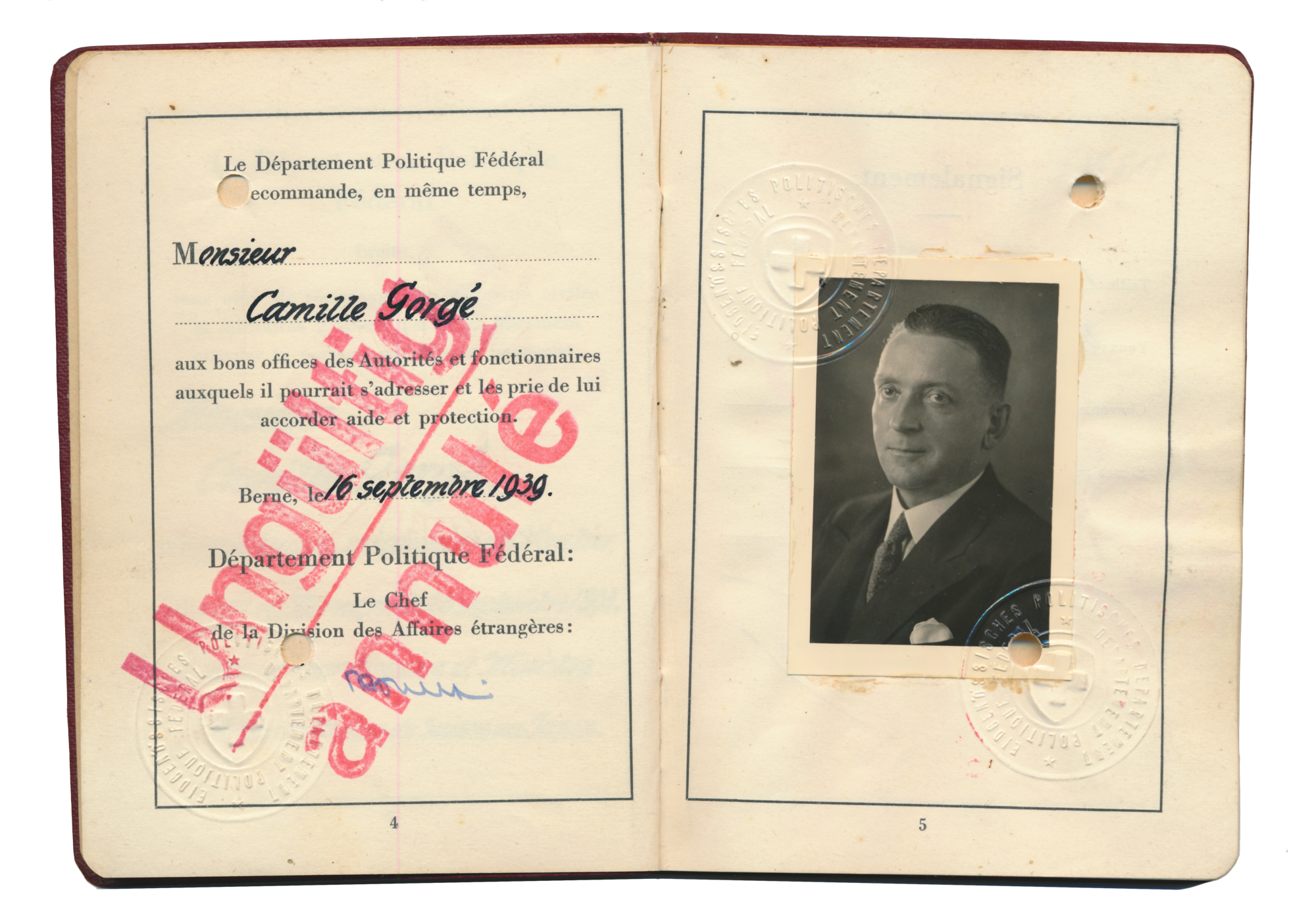

Camille Gorgé's diplomatic passport, late 1939 (©Gorgé family archives)

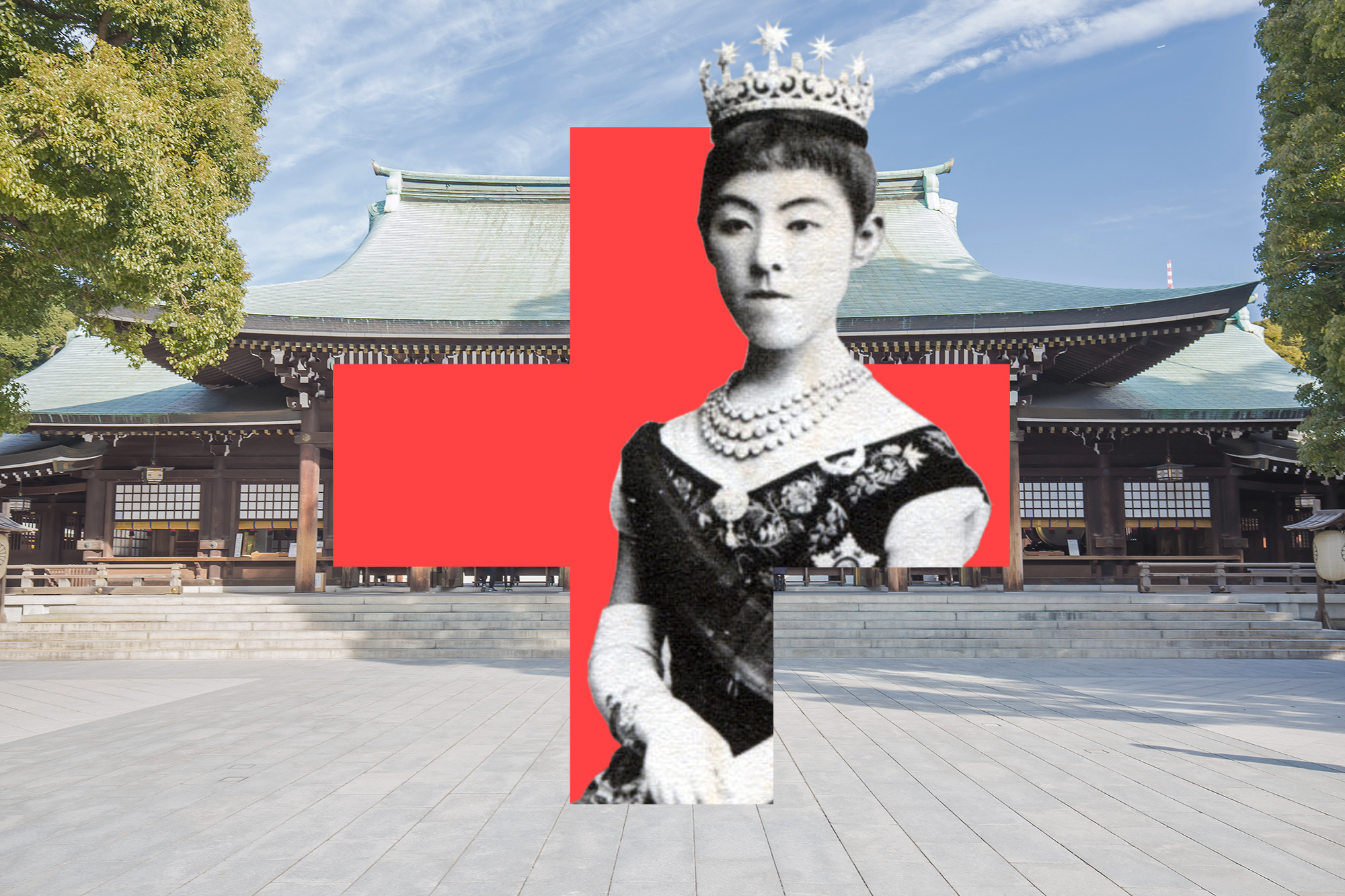

Have you ever wondered what happened to foreign diplomats in Japan when the Asia-Pacific War broke out? While foreign residents left the Empire in the late 1930s, others, such as the members of the Swiss representation, stayed. Switzerland had had diplomatic relations with Japan since 1864, first through a consulate, and since 1906 through a legation. Being a small State and not a great power, Switzerland, according to diplomatic etiquette, did not station an Ambassador in Japan, but a diplomat in the rank of a Minister (one rank below), who headed the Legation of Switzerland in Tokyo (first in Koji-machi, then in Mita from 1942).

The Swiss Legation in Mita (©Gorgé family archives)

On February 15, 1940, a new Minister, Camille Gorgé (1893-1978), took office in Tokyo. Since his first stay in Japan in the 1920s, Gorgé had dreamed about this position, as he considered the Japanese civilization as one of the world’s most fascinating and sophisticated. However, he quickly realized that 1940s Imperial Japan, with its military dictatorship and rampant xenophobia, would be one of his most difficult missions.

Camille Gorgé, his wife Rosine, and the staff of the Swiss Legation in Japan (©Gorgé family archives)

Last man standing

The situation worsened following the start of the Pacific War, when the two hundred remaining Swiss citizens in Japan found themselves unable to evacuate the archipelago and were increasingly exposed to arrests, bullying, imprisonment, torture, and rationing - despite their country’s neutrality. Nevertheless, the Swiss government asked Gorgé to stay, protect the Swiss citizens there, and maintain Switzerland’s presence in view of the post-war era. From tense meetings with the Japanese State Police to Swiss National Day celebrations held in his residence, the Minister spared no efforts to guarantee the rights and good morale of his compatriots.

February 7, 1941: Camille Gorgé offers a portrait of Swiss pedagogue and reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi to Professor Arata Osada, who popularized his methods in Japan (©Gorgé family archives)

One of Camille Gorgé's many sketches (©Gorgé family archives)

Most importantly, however, he and his Legation were given another massive yet crucial task: lending Switzerland’s “Good Office” to friendly nations that were at war with Japan; in other words, acting as an intermediary and a “protective power” between the Japanese Empire and the Allied Powers on matters of common interest. Gorgé thus regularly met with Japanese officials to organize exchanges of civilians, diplomats, and prisoners of war. He conducted negotiations in the name of the USA, Great Britain and other Allied Nations, and he ensured the respect of international conventions.

Minister Camille Gorgé in his office (©Gorgé family archives)

A strange holiday retreat

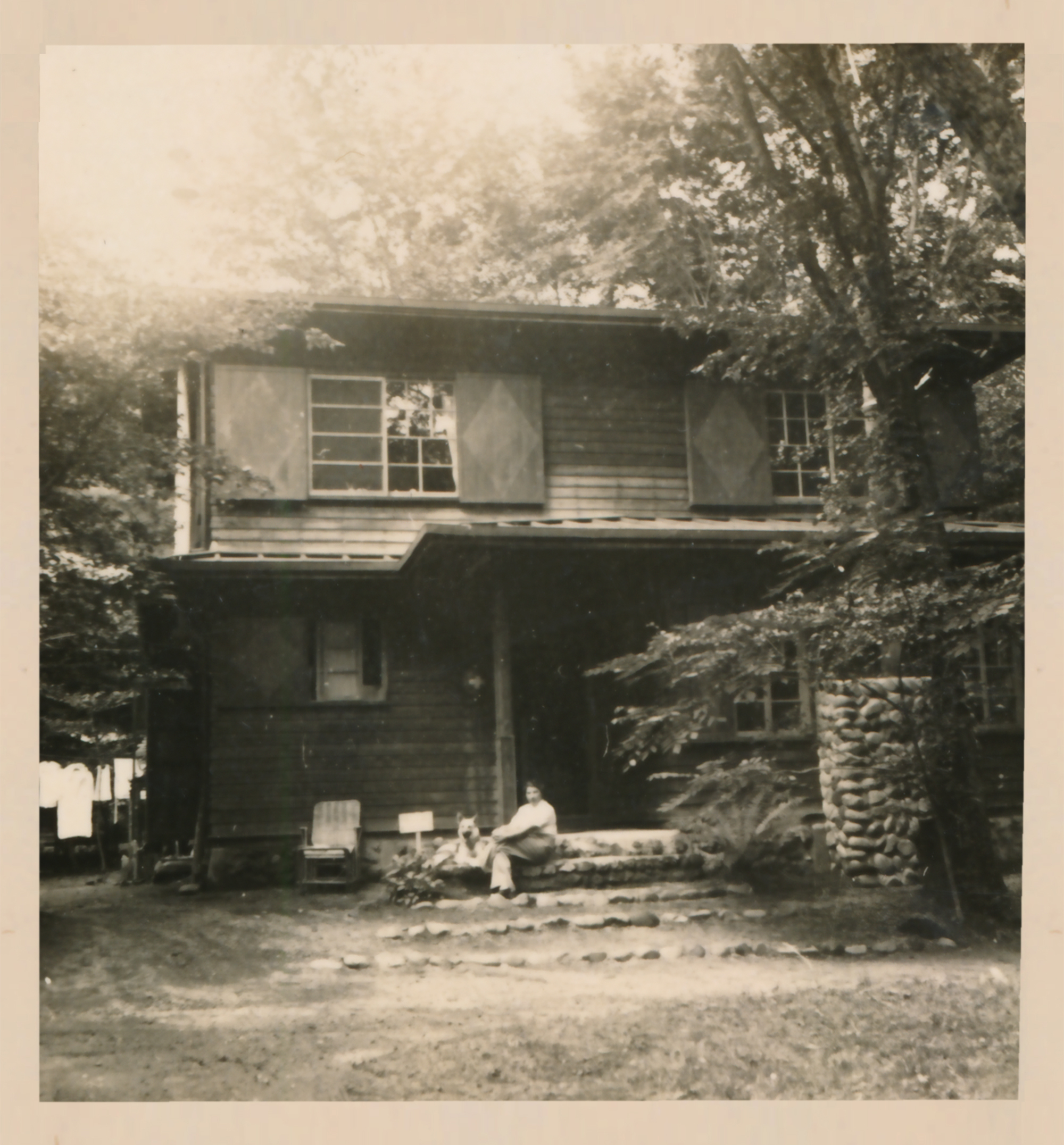

In summer of 1944, due to the ever-increasing frequency of Allied bombings, the Japanese Imperial Government evacuated all foreign together with their families from Tokyo to Karuizawa, a village located in the mountains of Nagano prefecture, where most diplomatic heads of missions had their holiday residences. Miyama-so, a large villa built there in 1942 by Japanese businessman Eijiro Maeda (1874-1961), became the new office of Camille Gorgé and the Swiss Legation until the end of 1945.

Camille Gorgé, his wife Rosine and their chauffeur in the Japanese Alps (©Gorgé family archives)

Camille Gorgé's hut in Karuizawa (©Gorgé family archives)

The building of the Swiss Legation in autumn 1945, after Japan's capitulation (©Karuizawa City / University of Tsukuba)

Despite food shortages and military police surveillance, none of the Swiss evacuees fell victim to air raids. However, up until the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs opened a branch office in the village to cater to the needs of foreign residents, Swiss citizens received little food from the Japanese government, and often had to rely on the few diplomatic bags (e.g. food, emergency supplies, documents) sent by the Swiss government that actually managed to find their way to Japan. Nevertheless, Karuizawa residents, who were accustomed to foreign visitors from prewar times, are said to have behaved cordially with the Legation and the Swiss community, proving that the Swiss-Japanese friendship can resist even the most difficult times of war.

Memories of Karuizawa

The building of the Swiss Legation as it stands today (©Karuizawa City / University of Tsukuba)

Following the capitulation, the Swiss Legation returned to Tokyo and finished their mandate as protective power by helping American citizens with consular matters. After that, all foreign legations and embassies were dissolved by the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, and no diplomatic missions were allowed to maintain contact with the Japanese Government. While a few Swiss diplomats remained as representatives and established their new quarters in what would later become the Embassy of Switzerland, Camille Gorgé left for his next diplomatic post in Ankara. As for the Miyama-so, it was acquired for 210,000,000 JPY (roughly 2 Million CHF) by the Karuizawa Town Administration in 2007, to avoid its destruction by its previous owner. The building was officially classified as a historic site in 2015.

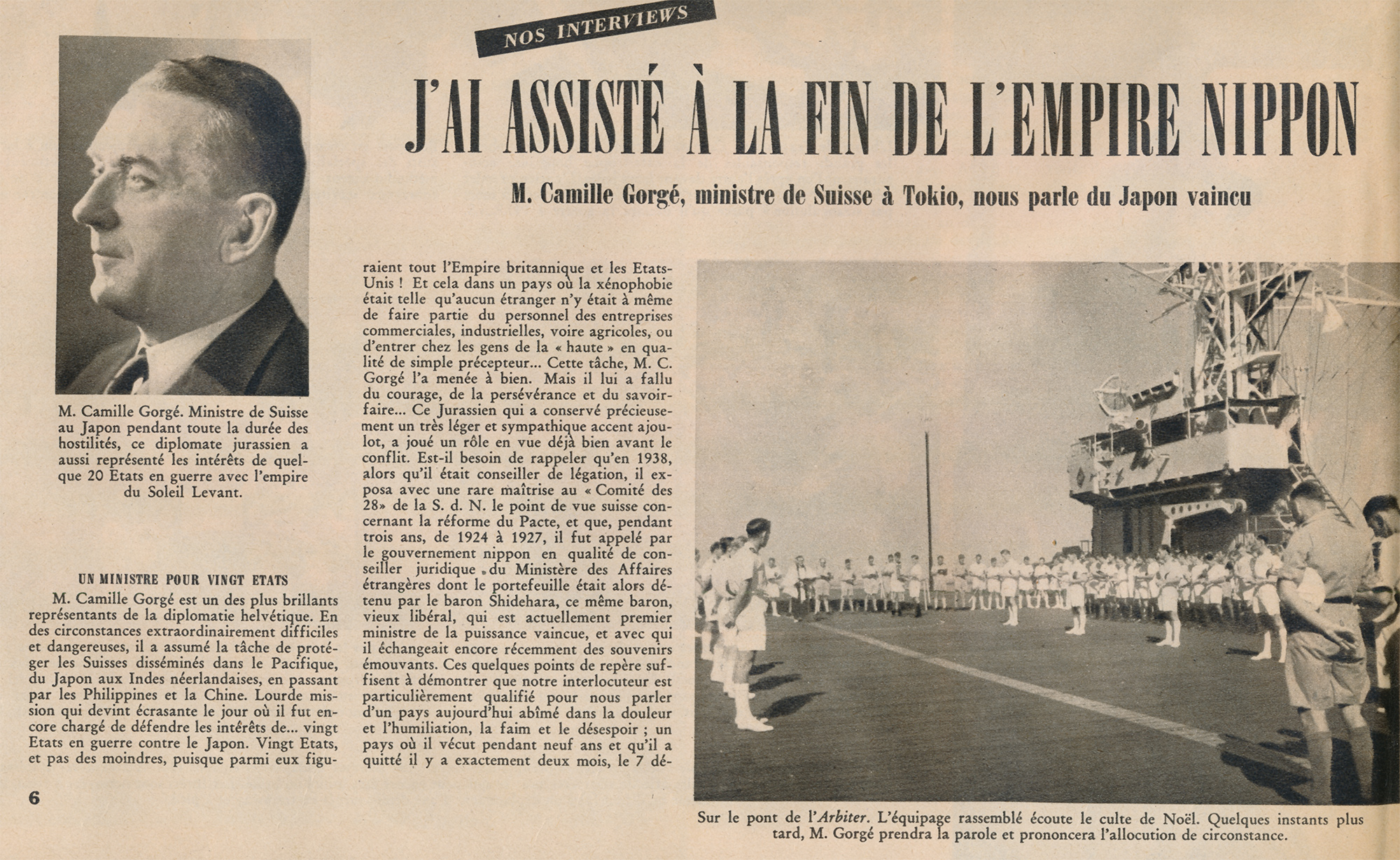

Camille Gorgé recounted his experience in Japan to Swiss newspaper in early 1946, shortly after the end of its mission in Tokyo (©Gorgé family archives)

In 1947, Camille Gorgé compiled reports and diary entries from January 7, 1940, to October 2, 1945, into his memoirs. These were published in 2018 by a group of researchers from the University of Fribourg in a shortened and annotated version, and in full length online by the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland (www.dodis.ch). Gorgé’s memoires “Journal d'un témoin - Camille Gorgé, diplomate suisse dans le Japon en guerre (1940–1945)” ("Diary of a Witness - Camille Gorgé, a Swiss diplomat in Japan during World War II (1940-1945)") are an elegant and personal account of wartime Japan, and offers a new and unique perspective on Swiss-Japanese bilateral relations!

Pierre-Yves Donzé, Claude Hauser, Pascal Lottaz et Andy Maître (Ed.): «Journal d'un témoin». Camille Gorgé, diplomate suisse dans le Japon en guerre (1940–1945), Quaderni di Dodis 10, Bern 2018, dodis.ch/q10

Source: Pierre-Yves Donzé, Claude Hauser, Pascal Lottaz et Andy Maître (Ed.): «Journal d'un témoin». Camille Gorgé, diplomate suisse dans le Japon en guerre (1940–1945), Quaderni di Dodis 10, Berne 2018.

Links

- Annotated Memoirs of Camille Gorgé (free) [FR]

- Original Memoires of Camille Gorgé (free) [FR]

- The 1st Japan-Swiss Academic Workshop - “Solving the Mystery of the Former Swiss Residence Miyama-so: Its Historical Significance and Role”

- Embassy of Switzerland in Japan

- Switzerland’s current protective power mandates